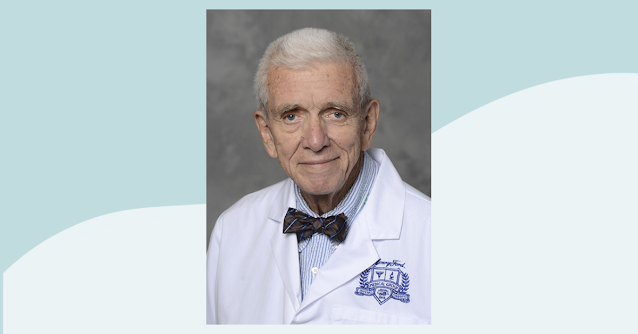

Dr. Fred Whitehouse: Historical Endo Extraordinaire

It's not often you get to meet someone who actually worked directly with Dr. Elliott Joslin, "the father of diabetes care," back in the day. But that is Dr. Fred W. Whitehouse, a gentleman who's made an incredible impact on treating diabetes for more than seven decades. You might call him an Endo for the Ages, someone who connects the past to the present and moves us toward the future in the world of diabetes.

For Dr. Whitehouse, his first encounter with diabetes came at the age of 12, when his 8-year-old brother was diagnosed during a family car trip from Arizona and California. This was long before the idea of adding "Dr." to the front of his name was even on the mind -- before a career in diabetes, and before he'd find a place in the diabetes history books as an endocrinologist who's been at the forefront of D-care for more than a half-century.

Now 85, Dr. Whitehouse practices three days a week at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

He took some time recently for a chat with us at the 'Mine, and our 90-minute discussion hit on just about every topic in the diabetes world, from his own family connections, to his humble medical career beginnings at the Joslin Clinic — working directly with the legendary Dr. Joslin himself! — to the evolution in care and research he's observed and helped shepherd in through the decades, his American Diabetes Association presidency, and even D-Camp, the Diabetes Online Community and his thoughts on how close we are to a cure. I'll do my best to summarize his exceptional journey here for you.

In fact, his journey unofficially began in August 1938 on that summer drive with his family, when his younger brother Johnny suddenly needed frequent stops to use the bathroom. Mom knew it was diabetes because one of her cousins had been diagnosed young and died in 1919 after slipping into a coma in Connecticut while on the way to see a "famous doctor" in Boston. Thankfully, Whitehouse's own brother's diagnosis came more than a decade after insulin's discovery, and a young Fred was determined to help take care of him.

"I was the resident chemist in our family because I had an amateur chemistry set and would boil the urine, trying to get the color blue because that meant no more sugar in the urine," he said. "That was my initiation into diabetes."

But then, years went by and he didn't think about diabetes as a career-influencer. Instead, he wanted to go into obstetrics. "There's nothing more delightful than delivering babies," he says. But Whitehouse soon found himself at Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago, where Dr. Rollin Woodyatt was the leading physician for patients with diabetes, who most docs of those days weren't comfortable caring for. His own days caring for his brother Johnny came back, and his destiny seemed to fall into place.

After a stint as a Navy flight surgeon in the Korean War following his residency in Detroit, Whitehouse took a fellowship in Boston, MA, at the New England Deaconess Hospital — which shared space at 84 Bay Street with the Joslin Clinic at the time, about three miles from the site Joslin would later make its home. It was there that Whitehouse spent 15 months, working not only with a lineup of trailblazers from diabetes history but Dr. Elliott P. Joslin himself.

|

| Dr. Eliot Joslin with young patient |

At the time because of his age (mid-80s), Dr. Joslin spent most of his time in his office, but Whitehouse and the others would accompany him on the rounds when Joslin did see patients. Whitehouse recalls talking with Dr. Joslin about his entry into the D-field in the late 1800s, how his aunt had diabetes and motivated him to focus his medical career on the condition. And thank goodness he did!

"The old gentleman was still hale and hearty, and worked every day at the hospital doing his rounds every Saturday morning starting at 8 a.m. He really was a remarkable man," Whitehouse says of the legendary Joslin.

Whitehouse actually practiced with the "Big Four" of the time — Drs. Joslin and Howard F. Root who administered the first insulin delivery in the '20s, Priscilla White who revolutionized pregnancy and diabetes care, and Dr. Alexander Marble who focused on DKA and research. Later, Drs. Robert F. Bradley and Leo P.Krall and Joslin's son Allen joined the historical group that Whitehouse witnessed firsthand.

"Really, the strength of Joslin was the distinguished group he accrued who were high-quality, experienced, and specialized people in diabetes, not just some physicians who saw it on the side," Whitehouse says. "That team approach, the idea of focusing on high control of treatment, was what Joslin became known for. There were no clinical trials then and the thought was that complications may be hereditary, but that it could be controlled by intense care. But that wasn't proven by data for almost 40 years."

Back then, about three decades before home blood meters came onto the scene, it typically took about an hour to take a BG test in a clinic. At Joslin, Whitehouse said one could get that done in as quickly as 30 minutes. In those days, the color blue (dark blue, to be exact) was the goal because it suggested "normal blood sugar" and no glucose in the urine. He laughs now how many in the diabetes community advocate for the color blue and the International Diabetes Federation's Blue Circle, since it has a significant part in the pages of diabetes history!

Whitehouse left Joslin in September 1955 and went to work at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, where he remains today. He served more than 30 years as chief of the Endocrinology Diabetes Bone Mineral Disorders Division from 1962 to 1995, and has long been regarded as one of the nation's leaders in the field of diabetes.

He served as ADA president in 1978-79, and during his presidency the concept of ADA professional section councils — subgroups of members focusing on such specialties such as foot care, youth, pregnancy or complications. His honors include: the Banting Medal, Outstanding Clinician Award and Outstanding Physician Educator Award from the American Diabetes Association, and the Master Physician distinction from the American College of Physicians. The Henry Ford endocrinology division website says this about him: "Over the course of 60 years, Dr. Whitehouse has helped change the face of diabetes management and treatment." The Detroit hospital has even named a distinguished service award after Dr. Whitehouse!

Notably, Dr. Whitehouse was involved in testing human insulin in the late 1970s, and along with one of his colleagues in Detroit, treated the patient who was the second-ever person to take human insulin (the first was in Kansas). He also treated some of the earliest patients ever treated with insulin who would utilize new tools such as the first-ever blood meters and insulin pumps, as well as those who had transplants of various natures. The first patient with diabetes to receive a transplanted kidney at Henry Ford Hospital did so on Oct. 31, 1974, and he says it was a great success — that woman lived a full life for 14 years before succumbing to a massive heart attack.

One of his other D-patients was Elizabeth Hughes Gossett, diagnosed at age 11 in 1919 and one of the first to ever receive insulin from Dr. Fredrick Banting in 1922. She married William T. Gossett, who was general counsel for Ford Motor Company and lived in southeast Michigan. Before her death from pneumonia in 1981 at the age of 73 (totaling an estimated 42,000 insulin shots before her death), she saw Dr. Whitehouse but actually kept her health and diabetes a secret from the world. She was a "closet diabetic," Whitehouse says.

That was perhaps the way then, but now with the advent of the Internet and the diabetes online community, PWDs tend to be more enthusiastic about sharing their stories and are looking to connect. Whitehouse thinks support and mental health is important, and though he's not sure if there's enough follow-up data to judge the clinical significance of something like the diabetes online community, he does think it sounds like a positive influence — much like diabetes camps.

"There are far less closet diabetics than there used to be, and people are more open. That's a good thing because you can learn from others who are going through similar experiences."

(DBMine: EXACTLY!)

Whitehouse was also one of the initial endos participating in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trials (DCCT) in the 1980s — government-funded clinical trials that led to the proof that better managed diabetes could delay or even eliminate complications. Whitehouse says not everyone in the medical field supported that theory or thought the study was worthwhile. Those naysayers got a big "I told you so" years later when the A1c became the standard to gauge a person's management.

"They thought the question had been answered in their own mind and they didn't want to be bothered," he said. "But we had to be able to prove this with science and data for everyone, rather than it being one doctor from one or two places saying this was their opinion. The time for scientific proof had come."

Looking back, Whitehouse describes the DCCT as the most remarkable study ever supported by the NIH, which is ongoing and now in its 30th year. (See the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study that has continued following most of the original DCCT participants).

Whitehouse says he's amazed to have witnessed all the technological and daily care changes that have happened since he began in 1955, and that patients and physicians have much more basic knowledge about management. He believes the next leap forward will be just as amazing — prevention of type 1 and helping type 2s avoid complications with better management.

As far as moving toward a cure, Whitehouse has some thoughts on that, too.

"I think prevention of type 1 diabetes will come first," he said. "Then, better control of daily swings in blood glucose and better control over low blood sugar spells. Perhaps third will be better control of overweight and obesity. Last in my view will come the 'cure of the insulin-dependent diabetic person.' This will require stem cells from the diabetic's own tissues developing into beta cells, then preventing these 'personal' beta cells from being killed off as they initially were. This will be the crowning achievement. That's all coming, but I think diabetes will be around for a spell."

* Sadly, Dr. Whitehouse passed away on March 1, 2019. *

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Originally written by Michael W. Hoskins and published at DiabetesMine on March 22, 2012

Comments